Robinson JR, Jermin PJ

Volume 1 | Issue 2 | Aug – Nov 2016 | Page 35-46.

Author: Robinson JR[1], Jermin PJ[1].

[1] Avon Orthopaedic Centre Bristol, UK.

Address of Correspondence

Mr James Robinson, MB BS, MRCS, FRCS(Orth) MS

Avon Orthopaedic Centre, Bristol, UK

Email: info@KneeSpecialists.co.uk

Abstract

The menisci provide tibio-femoral joint congruity, stabilisation, shock absorption and proprioception. These functions are reliant on firm attachment to the tibial plateau at the meniscal roots. Meniscal root tears result in similar biomechanical consequences to total meniscectomy, but they remain easy to miss clinically and radiological evaluation may be unreliable. Different repair techniques are becoming more reproducible and laboratory studies have shown that the load bearing function of the menisci may, following adequate repair, be returned to approximate that of the intact knee. Whilst techniques continue to evolve, a lengthy period of protective post-operative rehabilitation remains necessary. It is hypothesized that restoration of the ability of the meniscus to dissipate load through the distribution of hoop stresses is projective of adjacent hyaline cartilage and the development of degenerate joint disease. subsequent progressive joint failure that may occur if they are left untreated.

Keywords: Meniscal Root Tear, Meniscal repair.

Introduction

The vital role meniscal integrity plays in the function of a healthy knee is well understood. As a result surgical treatment of meniscal tears has progressed. Previously, open total meniscectomy was performed for meniscal tears, however, the 132 fold increase in the rate of knee replacement that resulted condemned the technique to the annals of history (1). The treatment of meniscal tears now emphasises meniscal preservation when possible, with studies showing a reduction in osteoarthritis following meniscal repair as compared to tear resection (2). It has been demonstrated that tears of the meniscal root attachments de-function the effected meniscus and result in similar biomechanical consequences to total meniscectomy (3). Whilst the significance of meniscal root tears has long been recognised, it is only in the last decade that surgical techniques have evolved to allow the routine management of these lesions, aimed at improving symptoms and avoiding subsequent progressive joint failure that may occur if they are left untreated.

Meniscal Anatomy & Function

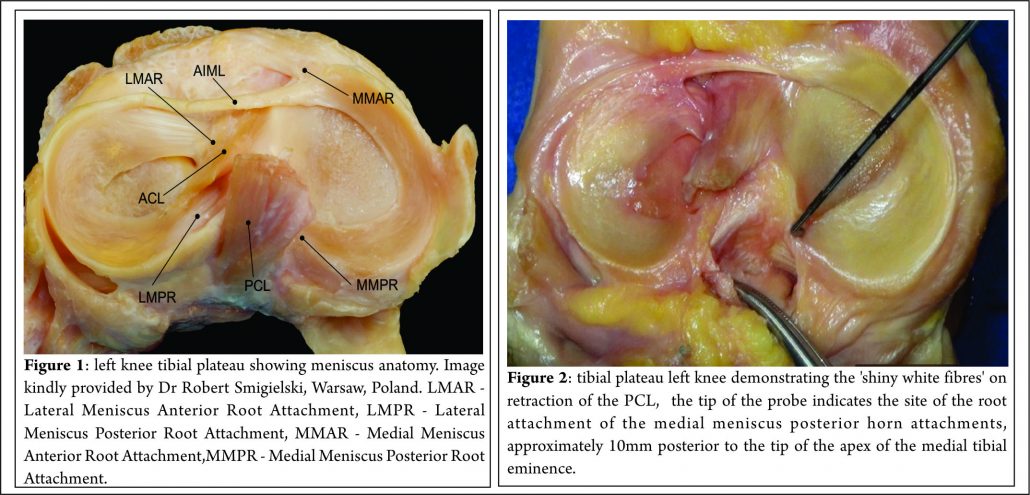

The menisci are 2 semi-lunar, fibrocartilage structures that surround the weight bearing surface of the medial and lateral tibial plateau (Fig. 1). They are wedge-shaped in cross section and crescent shaped in the axial plane. They are composed of 3 segments: an anterior horn/root, a body, and a posterior horn/root.(4,5). The medial meniscus is an asymmetric shaped structure, firmly attached to the joint capsule at its periphery (with, for example, the deep medial collateral ligament having both menisco-femoral and menisco-tibial fibres), thus rendering it relatively immobile and more prone to injury. The lateral meniscus is a much more symmetrical, incomplete O-shape and is less firmly attached making it a much more mobile structure to accommodate the increase in antero-posterior translation that occurs in the lateral compartment (during knee flexion, the lateral meniscus moves posteriorly by approximately 19mm, compared to only 4 mm for the medial meniscus (6)). Although the volumes of both menisci may be relatively similar, the lateral meniscus covers a significantly larger area of the tibial plateau than the medial meniscus (59% +/-6.8% vs 50% +/-5.5%) (7). The superior surfaces of both menisci are concave and thus congruent with the convex femoral articulation. The inferior surfaces are relatively flat, allowing them to effectively articulate with the tibial plateau (8,9). Each meniscus is composed of an interlacing network of collagen fibres, proteoglycans and glycoproteins. They are composed of approximately 75% water, 20% type I collagen, and 5% of other substances including proteoglycans, elastin and type II collagen (10,11). In a study examining bovine menisci, Andrews et al. (12) found that the ultra-stucture of the meniscus transitioned from highly aligned, longitudinally orientated collagenous fibres in the outer rim to a woven, less aligned structure in the inner meniscus. They found that the outer meniscus closely resembled a ligamentous structure, whereas the inner meniscus more closely resembled hyaline cartilage. The role of the menisci is to provide tibio-femoral joint congruity, stabilisation, shock absorption and proprioception (9). They are essential for joint preservation (1,2). As the knee is loaded, joint compression acts to extrude the menisci in a radial direction towards the periphery of the joint. “Hoop stress” in the circumferential collagen bundles resist this meniscal extrusion (5,9,10,11). Two types of fascicle organisation are seen – braided and woven (12). Braided structures result in increased stiffness with increased deformation owing to increasing friction. This organisation is well suited to the circumferential hoop stresses that the meniscus is exposed to during loading. The woven structure is commonly used to withstand compressive loads; it converts compressive forces into tensile forces. The distribution of hoop stresses by the circumferential fibres helps to transmit even axial loads across the joint surfaces and approximately 50-70% of the total weight transmitted through either compartment is transmitted through each individual meniscus (13). This dissipation of load is protective of the adjacent hyaline cartilage, but is completely reliant on firm attachment of the menisci to the tibial plateau. The anterior and posterior horns of each meniscus are securely anchored to the tibial inter-condylar region by strong ligamentous-like root attachments. The anterior root attachments have relatively simple, planar insertions into the tibial plateau while the posterior roots have complex 3 dimensional insertions. (9,12,14) Knowledge of the anatomy of the meniscal root attachments is essential when considering repair as anatomic root repairs restore cartilage contact areas and minimise peak cartilage contact pressures better than non-anatomic root repair (15). The meniscal roots have three parts: the ligamentous mid-substance (root ligament), the transitional zone between the root ligament and meniscal body, and the bony insertion of the root ligament at the tibial plateau. (16) The transitional zone between the root ligament and the meniscus is considered to be the weakest link of the meniscus root (16) and this may explain the common finding of radial tears in the position particularly in degenerate menisci. The roots are very well vascularised, comparable to the red-red zone of the meniscus(16).

Medial Meniscus Anterior Root Attachment

The anatomy of the anterior medial meniscus root attachment is variable with 4 different types described by Berlet & Fowler (17). In 59% of knees the meniscus attached to the flat portion of the intercondylar region of the tibial plateau (Type 1). In 24% of knees the meniscus attached on the downward slope of the medial articular plateau towards the anterior intercondylar area (Type 2). In 15% of knees the root attached on the anterior slope of the medial tibial plateau (Type 3). In 3% the meniscus was only anchored by the peripheral coronary ligament with no direct attachment to the tibial plateau (Type 4). The anterior horn root attachment was associated with the fibres of anteromedial bundle of the ACL in 59% of knees. The anterior intermeniscal ligament (AIML) has been found to connect the anterior horns of both menisci in around 46% of knees although in 26% of knees it has been shown to run from the anterior horn of the medial meniscus to the lateral aspect of the joint capsule, anterior to the lateral meniscus. The significance of the intermeniscal ligament is unclear (18). Poh et al. (19) sectioned the AIML and found no change in the tibio-femoral contact mechanics. The authors concluded that the anterior root attachments result in the menisci distributing loads independently of one-another. In a separate study, however, Paci et al (20) sectioned the AIML and did notice significantly raised contact pressures within the medial compartment of the knee. As its role remains uncertain, it would seem reasonable to preserve and protect it during surgery if possible.

Medial Meniscus Posterior Root Attachment

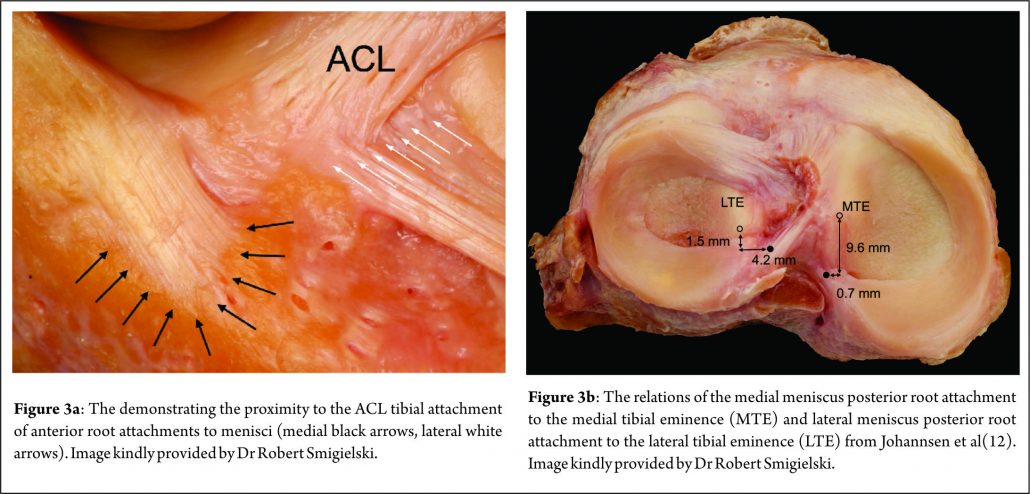

Johannsen et al. (21) reported that position of the medial meniscus posterior horn root attachment was a mean distance of 3.5mm lateral to the medial tibial plateau articular cartilage inflection point and 8.2mm anterior to the most superior position of the PCL attachment site and a mean distance of 9.6mm posterior and 0.7mm lateral to the apex of the medial tibial eminence. Adjacent to the attachment of the posterior root are what some surgeons term the “shiny white fibres” (Fig. 2). These are easily recognisable and appear distinct to the root attachment although are continuous with the main posterior root attachment. Whilst not part of the central root attachment, it has been demonstrated that these supplementary ‘shiny white’ fibres significantly contribute to the biomechanical properties of the native meniscal root(16).

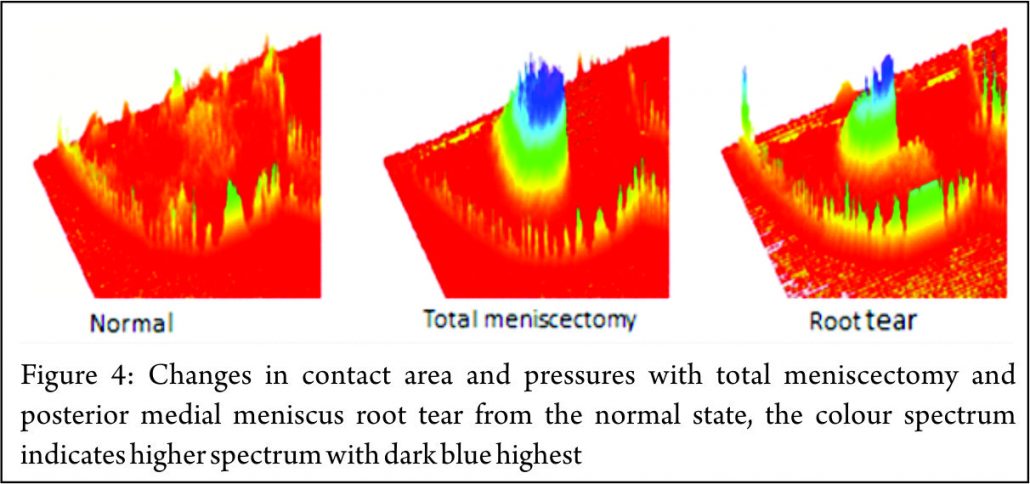

Lateral Meniscal Anterior Root Attachment

This attaches just anterior to the lateral tibial eminence and and is intimately related to the tibial attachment of the ACL (Fig. 3a) . Zantop (22) et al reported that the centre of the anteromedial (AM) bundle of the ACL was, on average, 5.2mm medial and 2.7mm posterior to the lateral anterior root; while the posterolateral (PL) bundle was 11.2mm posterior and 4.1mm medial to the anterior root. Various studies have noted that the anterior horn of the lateral meniscus attaches to the ACL in all knees, sharing approximately 60% of their attachment sites (9,22,23,24,25). The lateral meniscal anterior root attachment is smaller than the medial meniscal anterior root, with average footprints of 44.5 mm2 and 93 mm2 respectively. The proximity of the lateral meniscus anterior root attachment to the ACL tibial attachment means that an ACL reconstruction tunnel placed postero-lateral in the ACL tibial attachment site may significantly weaken or disrupt the LM anterior root attachment (15).

Lateral Meniscal Posterior Root Attachment

The lateral meniscus posterior root attachment is posteromedial to the lateral tibial eminence apex, medial to the lateral articular cartilage edge, anterior to the PCL tibial attachment and anterolateral to the medial meniscus posterior root attachment. (9,25,26). Johannsen et al (21) also reported the centre of the lateral meniscal posterior root to be an area 4.3mm medial and 1.5mm posterior to the lateral tibial eminence (Fig. 3b) . Three different attachment patterns have been described (16). In 76% of cases, two insertion sites were found with the predominant component attaching to the intertubercular area with anterior extension into the medial tubercle and the minor component attaching to the posterior slope of the lateral tibial tubercle. In the remaining 24%, there was a solitary insertion site to either the inter tubercular area or the posterior slope of the lateral tubercle.

Pathology & Epidemiology

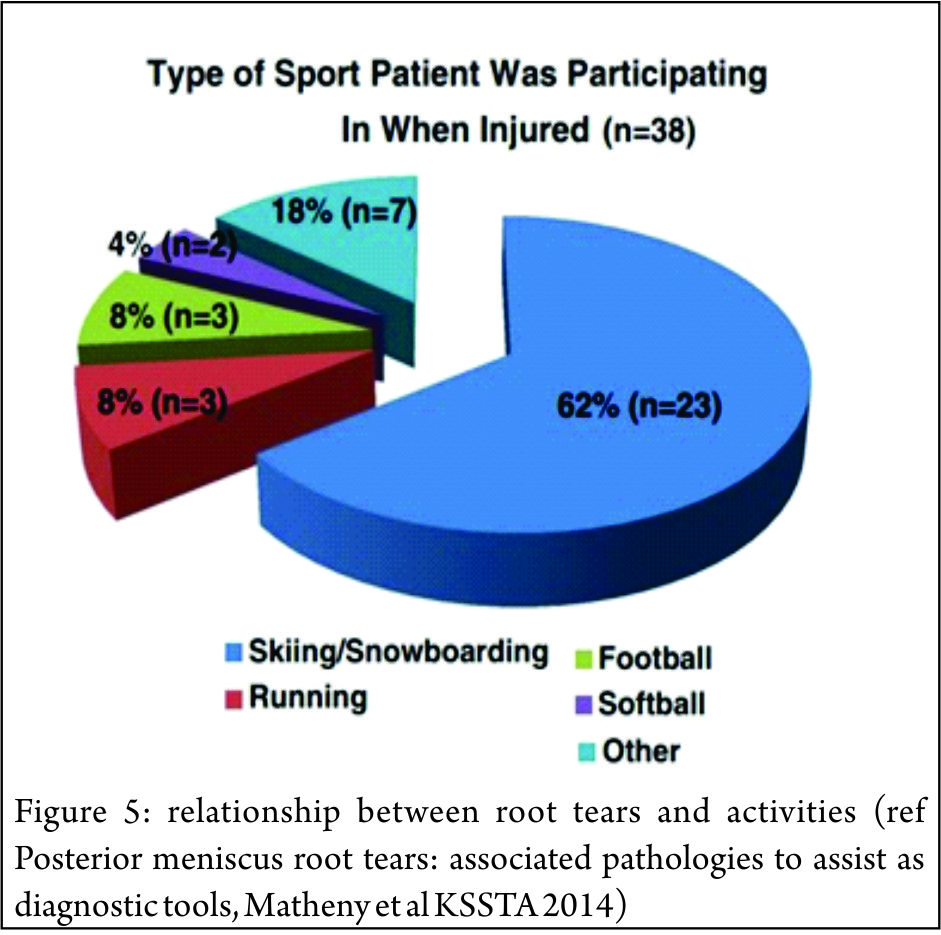

The principle mechanical function of the menisci is to convert compressive loads into hoop stresses and relies on their firm attachment to the tibial plateau. Thus, when the meniscus root is torn, there is no restraint to the peripheral distortion of the menisci and meniscal extrusion occurs. The biomechanical consequences are of a decreased contact surface between the tibia and femur and supra-physiological cartilage contact pressures, analogous to a total meniscectomy (3) (Fig. 4). In a normal knee, peak articular cartilage contact pressures are on average, 3841 kPa. In the context of a medial meniscal posterior root tear, this can rise to 5084 kPa. The contact area falls from an average of 594mm2 in the normal knee to 474mm2 when there is a tear of the medial meniscal posterior root (27). It has been demonstrated that contact pressures and contact areas may be normalised following meniscus root repair. (3,28,29,30) The sequence of joint failure is thought to be: a root tear occurs, this results in greater meniscal displacement and gap formation at the root avulsion site when compressive loads are placed across the knee. Over time the meniscus extrudes as a result of unopposed radial forces. This leads to a combination of altered knee biomechanics and significant increases in articular cartilage contact pressures within that compartment resulting in degeneration and osteoarthritis (31).

Anterior Meniscal Root Tears

Tears of the anterior roots are uncommon (11,32,33,34,35,36) but importantly, the anterior root attachment may be disrupted or weakened by iatrogenic injury (misplaced anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction tunnels and intra medullary tibial nailing entry sites being examples (15,37)). Medial Meniscal Posterior Root Tears. It is estimated that injury to the medial meniscus posterior root attachment may be present in 10-21% of arthroscopic meniscal repairs or meniscectomies (38,39,40). The true incidence may be higher owing to the limitations of current MRI to diagnose these tears. In addition the root attachment may not be routinely visualised by some surgeons who undertake knee arthroscopy. Increased age, female sex, raised BMI and varus alignment have all been associated with a higher incidence of medial root tears (38,39,40). Medial meniscus posterior root attachment tears are often more chronic and degenerate in nature, and may not be associated with an acute event.

Lateral Meniscus Posterior Root Tears

It has been suggested that the increased mobility of the lateral meniscus, results in the lateral meniscal root attachments being subjected to less stress than the medial side.(33,40,41). However the lateral meniscus is known to be an important restraint to the pivot shift (42) and injury to the lateral meniscus is implicated as a cause of the high grade pivot shift (43,44) Tears of the lateral posterior root have been observed in 7-9.8% of patients with an ACL rupture (45,46). The risk factors for tears here are largely unknown, associations with sporting activity and pivot-contact sports have been noted. (47,48) (Figure 5)

Diagnosis

Clinical Presentation

Clinical diagnosis of meniscal root tears remains challenging. The signs and symptoms that commonly manifest with typical meniscal tears may not be present with meniscal root tears. Patients may present with joint line tenderness but without mechanical symptoms. Lee et al (49) found that in their series of 21 patients with medial meniscus posterior root attachment tears, only 14.3% and 9.5% of their patients, respectively, complained of locking and giving way. Most patients with a medial root tear do not recall a specific event leading to their pain (50). On examination, the most commonly encountered signs are posterior knee pain with deep flexion (66.7%) and joint line tenderness (31.9%). McMurray’s test may be positive in 57.1% and an effusion present in only 14.3% of patients (49). Seil et al (51) described a novel test for medial meniscal posterior root avulsions: the patient was fully relaxed and the knee in extension; during varus stress testing, the anteromedial joint line was palpated and meniscal extrusion was reproduced. Extrusion disappeared when the leg was brought into normal alignment. The reliability of this test, however, is currently unclear and we have not found it to be particularly useful.

Diagnostic Imaging

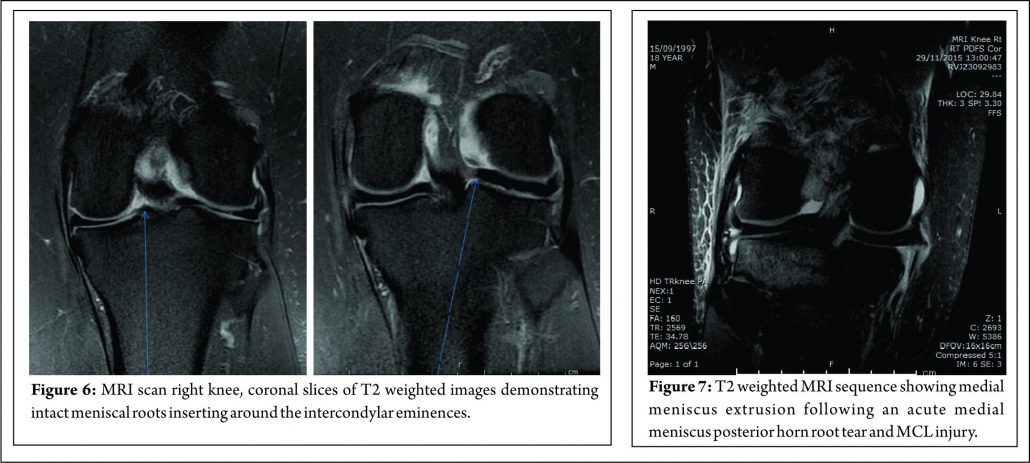

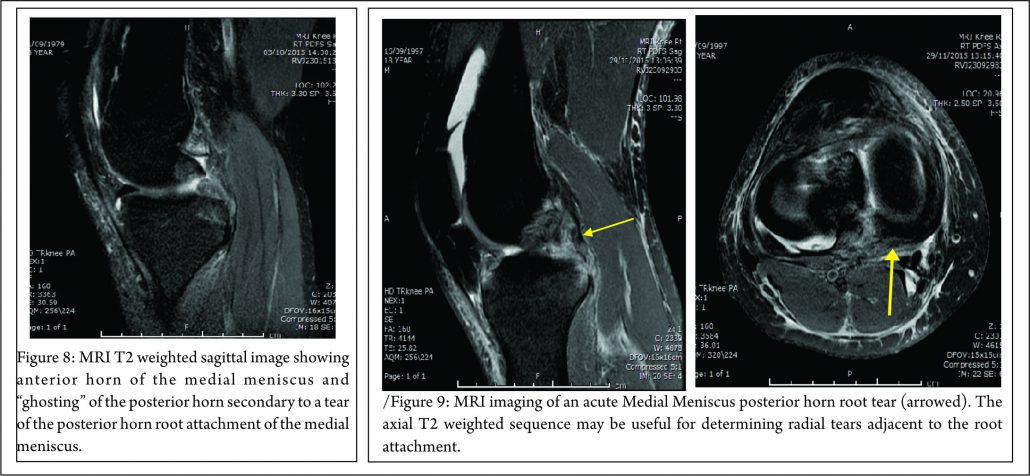

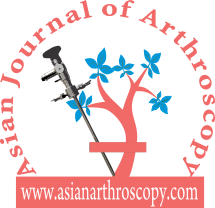

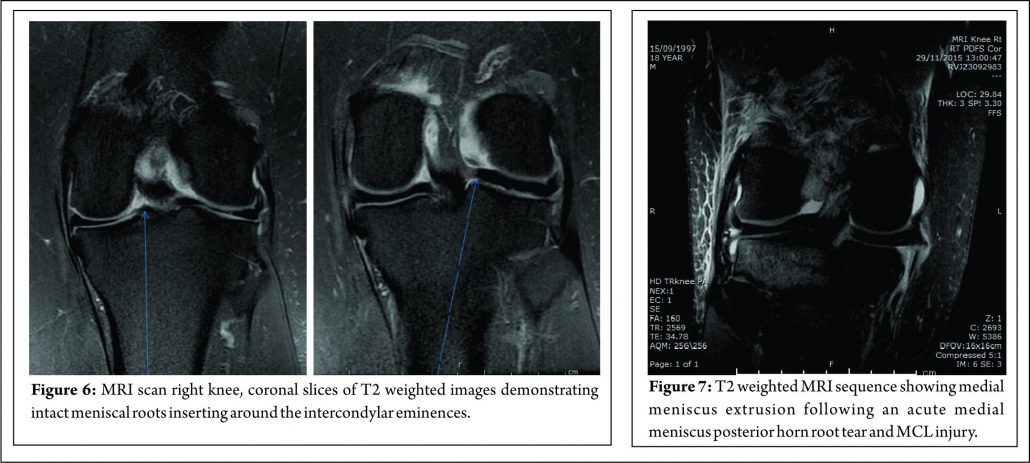

In addition to the difficulties of clinical diagnosis, accurate radiological diagnosis is heavily reliant on imaging quality and the expertise of the reporting radiologist. In a study of 67 patients with arthroscopy proven posterior medial meniscal root tears, only 72.9% were detected by pre-operative MRI scanning, the remaining patients showed degeneration and /or fluid accumulation at the posterior horn without a visible tear(40). The posterior root of the medial meniscus may be best visualised on 2 consecutive T2 coronal MRI images as a band of fibrocartilage anchoring the posterior horn to the tibial plateau (Fig. 6). Meniscal root tears may be difficult to visualise directly and the relatively small size of the meniscal roots means that tears may be missed by standard 2 mm MRI sections. The presence of medial meniscal extrusion has been described as having a high correlation with the presence of a posterior root tear (Fig. 7) Meniscal extrusion is defined as partial or total displacement of the meniscus from the tibial articular cartilage. (52,53) More than 3mm of meniscal extrusion, on mid-coronal imaging, has been shown to lead to articular cartilage degeneration and is associated with complex meniscal tear patterns and tears of the posterior roots (53,54). Not all cases of meniscal extrusion, however, are a result of root tears. Magee (55) hypothesised that there may be a group of patients who stretch their meniscal roots, leading to extrusion but without a frank tear. Meniscal extrusion is less common in lateral tears for a number of reasons.

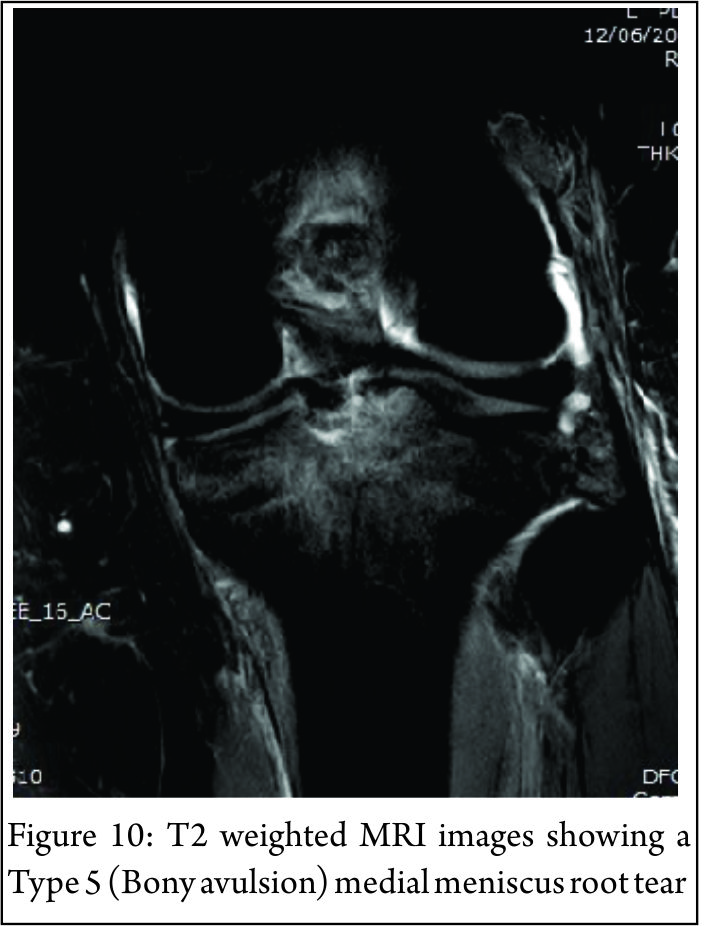

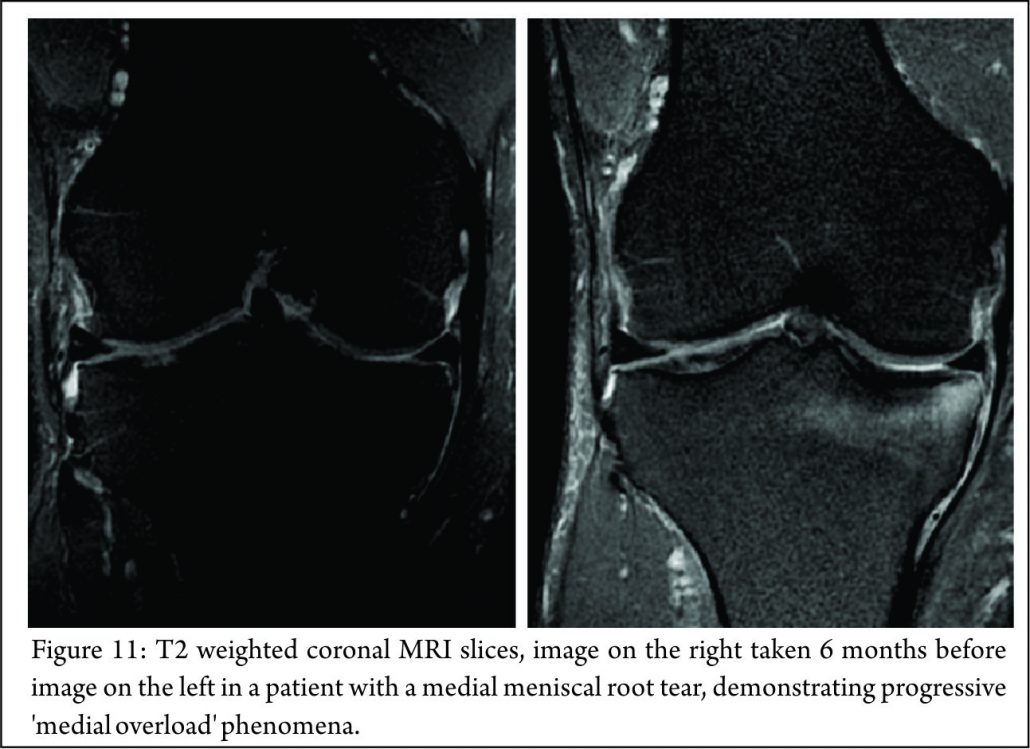

The lateral compartment is subject to lower contact pressures than the medial side and hence lateral extrusion is less likely to occur. In addition to this, the lateral posterior root has further anchorage from meniscofemoral ligaments. They provide additional restraint to extrusion with a reported rate of 14% lateral meniscal extrusion if they are intact (56). If the meniscofemoral ligaments are not present or torn, in the setting of a posterior root tear, the extrusion rate of the lateral meniscus quadruples and approaches that of the medial meniscus. Another surrogate sign of a root tear is a ‘ghost sign.’ (Fig. 8) On a sagittal MRI cut, both the anterior and posterior horns should be visible. If the anterior horn is present but the posterior one is not, it is termed a ‘ghost meniscus.’ This finding is highly suggestive of a root tear and will often be found in tandem with extrusion on the coronal cuts (54,57). We have also found that the axial T2 weighted sequence to be useful for identifying meniscal root tears, particularly radial tears adjacent to the meniscal root. (Fig. 9). Tibial bone marrow oedema may be noted adjacent to the root attachment in acute meniscal root avulsion (Fig. 10). Bone marrow oedema, seen more peripherally in tibia, or affecting the medial femoral condyle may develop as the result of overload within the compartment, as a result of loss of meniscal function following a medial root tear (Fig. 11)

Arthroscopic Assessment of the meniscal root attachments.

Due to the difficulties of accurate clinical and radiological diagnosis, the gold standard for determining the presence of a meniscus root tear remains arthroscopic assessment (55).

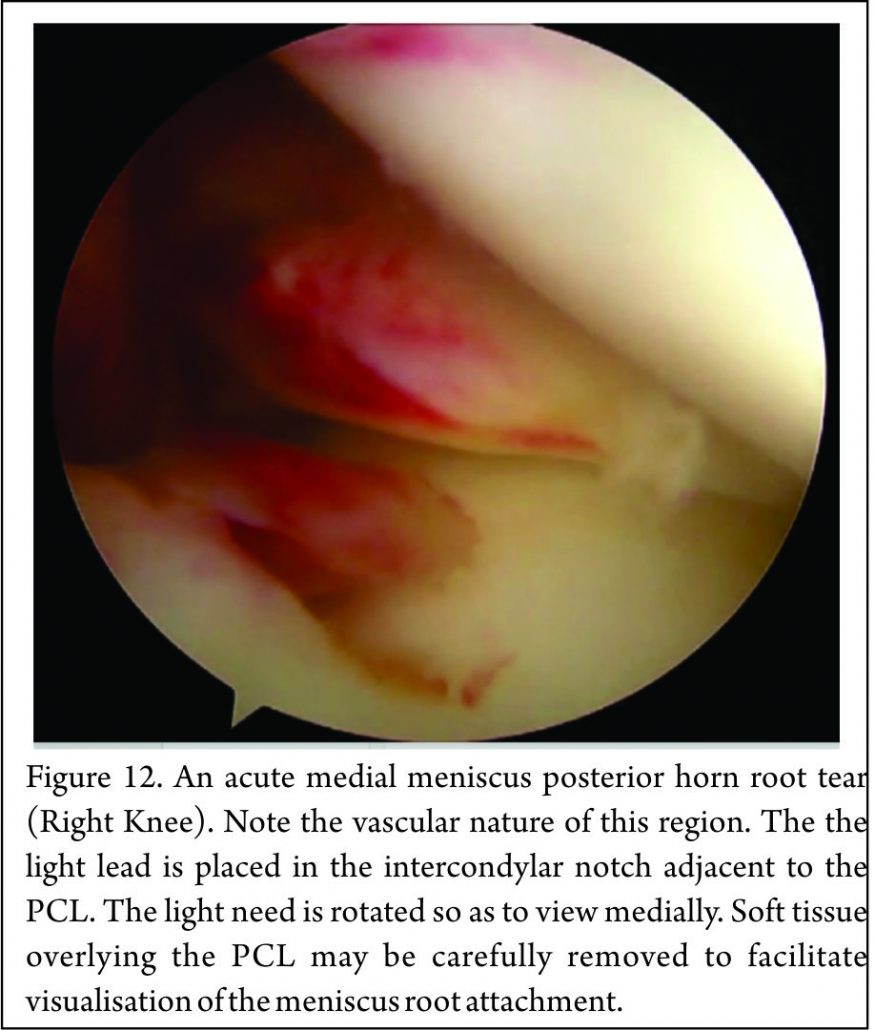

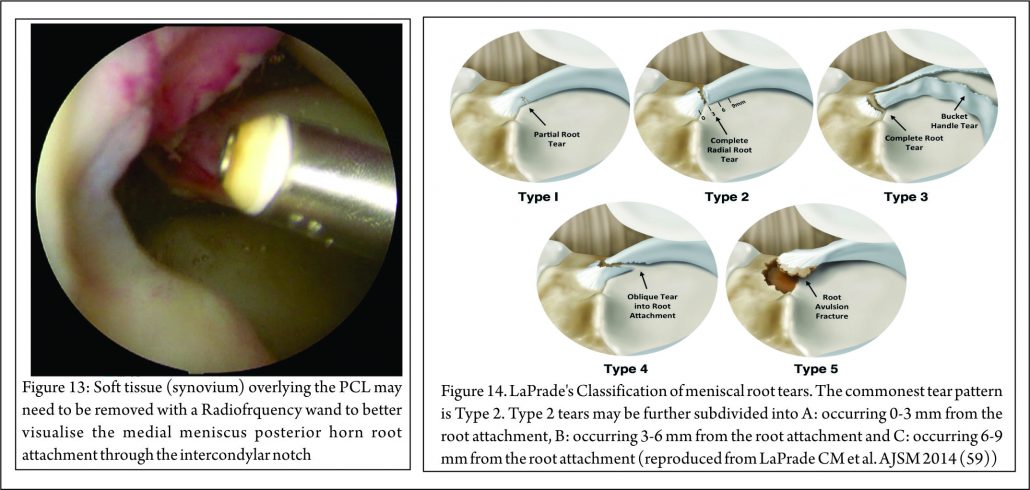

Placement of the anterolateral arthroscopy portal high and adjacent to the patella tendon facilitates viewing of the medial meniscus posterior horn root attachment with the arthroscope placed in the intercondylar notch, adjacent to the PCL (Fig. 12). Sometimes soft tissue (synovium and fat) overlying the PCL may need to be removed with either shaver or radio-frequency ablation device to improve the view of the posterior root attachment of the medial meniscus (Figure 13). The senior author has not found a “reverse notch plasty” (as described by some authors (58)) to be necessary, however, a medial collateral pie crusting is almost always required for medial posterior horn root repair.

Classification

The most commonly used classification system for posterior root tears is the LaPrade classification (Figure 14) (59). This is an anatomic classification system: Type 1 (7% of tears) are partial thickness, stable root tears. Type 2 (68% of tears) are complete tears within 9mm of the root attachment; this is further subdivided into 2A, 2B & 2C, located 0-3, 3-6 & 6-9mm respectively from the root attachment.

Type 3 (6% tears) are a bucket handle tear with complete root detachment. Type 4 (8% tears) are complex oblique tears with complete root detachments extending into the root attachment. Type 5 (8%) are bony avulsion of the root. This classification is purely anatomical and does not offer a guide to treatment or prognosis. West et al. classified lateral meniscus root tears associated with an acute ACL injury. Three types of tear were identified at arthroscopic assessment: Type 1 were root avulsions. Type II were isolated radial split tears within one centimetre from the root insertion. Type 3 were complete root tears with radial and longitudinal elements (60). Another classification has also been described relating to the integrity of the menisco-femoral ligaments (MFL): Type 1 tears are avulsions of the root. Type 2 are radial tears of the lateral meniscus posterior horn with an intact meniscofemoral ligament. Type 3 is complete detachment of the posterior meniscus horn (61). Again these classifications are descriptive and do not, yet, guide treatment or prognosis, although it is suggested that lateral meniscus posterior root tears, in which the meniscofemoral ligament remain intact, may not require treatment.

Treatment

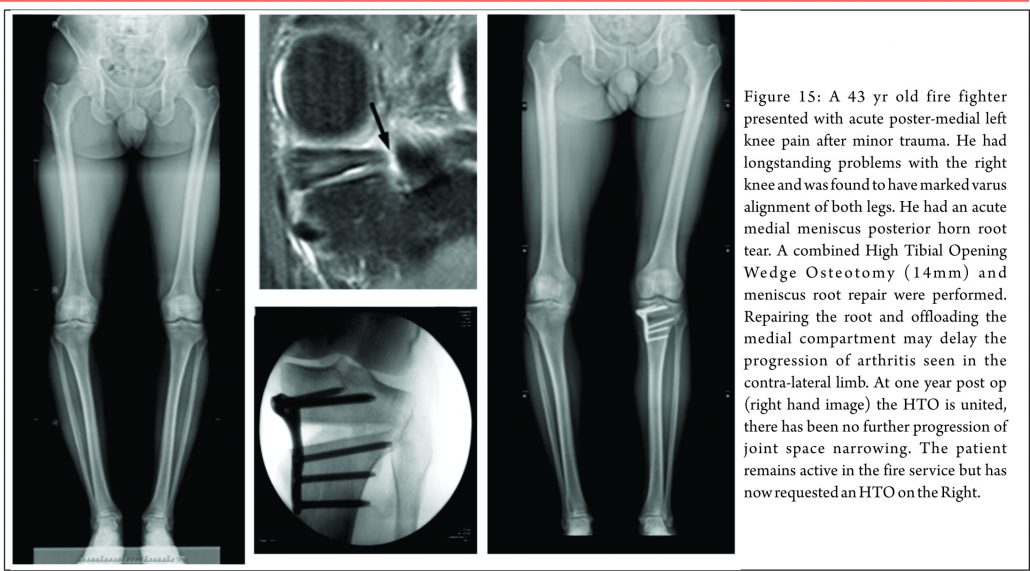

There are three treatment categories for meniscal root tears: non-operative, partial meniscectomy and meniscal repair. Historically, the first two options have dominated. Non-operative treatment of these injuries still has a role. In poor surgical candidates (multiple co-morbidities, advanced age or significant underlying degenerative joint disease) an initial trial of non-operative treatment remains an appropriate first line treatment. When considering surgery, particularly when repairing these tears, it is important to appreciate any coronal plane malalignment that may be present in the patient. For example: repairing, and not offloading, a posterior medial root tear in a patient with significant genu varum, may be at higher risk of failure unless a concomitant corrective osteotomy was undertaken to offload the compartment and the repair (Fig. 15)

Non-Operative Treatment

Non-operative treatment fails to address the abnormal biomechanical environment that these tears create, and may lead to progressive osteoarthritis (62). In certain groups of patients (elderly, the obese, poor surgical candidates, or patients with advanced underlying degenerative joint disease) non-operative treatment may be reasonable. Symptomatic treatment with NSAIDs (oral or topical), activity modification and offloading braces may alleviate the joint pain associated with root tears. Initial bone marrow oedema as a result of the changed loading in the compartment may settle.

Operative Treatment

Meniscectomy

Historically, partial or total meniscectomies have been performed for root tears, typically providing short-term symptomatic relief with unknown long term consequences. An recent retrospective study of 58 patients with medial meniscal root tears who underwent either meniscectomy or root repair reported that while both treatments significantly improved subjective outcome scores (Lysholm & IKDC scores, p < 0.05), the repair group had more improvement and less progression of arthritis at mean follow up at 4 years (30). For patients with chronic root tears and symptomatic grade 3 or 4 chondral lesions who fail non-operative treatment partial meniscectomy remains the treatment of choice. If resecting a root tear, care must be employed not to debride the whole footprint otherwise a functionally meniscectomised knee will be created. Advantages of partial meniscectomy over repair are decreased operative time, less taxing post op recovery regime and an earlier return to sports / activities.

Meniscal Root Repair

Meniscal root tear repair may provide symptomatic relief and reduce abnormal articular cartilage loads implicated in the development of degenerative joint disease. Indications for meniscal repair are expanding but at present the main indications for root repair are: (1) acute traumatic root tears in patients with no underlying arthritis, with the aim of preventing the development of arthritis & (2) chronic, symptomatic root tears in young/middle aged patients without significant pre-existing arthritis (23,63). Lateral meniscus tears are most commonly associated with ACL tears and should be repaired concomitantly. Medially there are usually two distinct injury patterns – acute & chronic. An acute tear is often associated with the multi-ligamentous injured knee, particularly a complete MCL tear where the meniscocapsular ligaments are intact but the meniscus is avulsed from the root (63). In this setting there is a clear indication for meniscal root repair to prevent progressive joint failure. Conversely, chronic injuries are much more insidious in nature and have been reported to result in rapid ipsilateral compartment cartilage degeneration if undetected (63). The treating surgeon must distinguish if the tear is causative or resultant from the arthritis, which can be a difficult distinction to make. If there are only early chondral changes on imaging with evidence of a root tear and meniscal extrusion, repair would be indicated to prevent progression of arthritis. The two most common methods of meniscal root repair are: transosseous suture repairs and suture anchor repairs. It is important to note that non-anatomical meniscal root repair has a substantial deleterious effect on meniscal function (64).

Suture Anchor Technique

This technique has a theoretical advantage that it does not involve drilling a tibial tunnel, which may be useful in the presence of concomitant ligamental reconstruction. It uses “all-inside” fixation, and avoids the need for a distal fixation which potentially places abrasive forces on the sutures used. The shorter menisco-suture construct may reduce micro-motion at the repair site (65) The technique does, however, require the placement of a posterior arthroscopic portal. The technique described by Engelsohn et al (66) used an accessory posteromedial portal. The repairs were tensioned using standard arthroscopic knot tying techniques from the anteromedial portal. The authors stated that in a ligamentously stable knee, the accessory (high PM) portal was necessary to achieve appropriate anchor placement. Others have reported a similar technique for repair of posterior medial root tears, with placement of high PM portal, approximately 4cm above the joint line and posterior to the medial femoral condyle, with insertion of a double-loaded metal suture anchor and suture passage using a suture hook and a shuttle suture(67).

Transosseous Tunnel Suture Repair

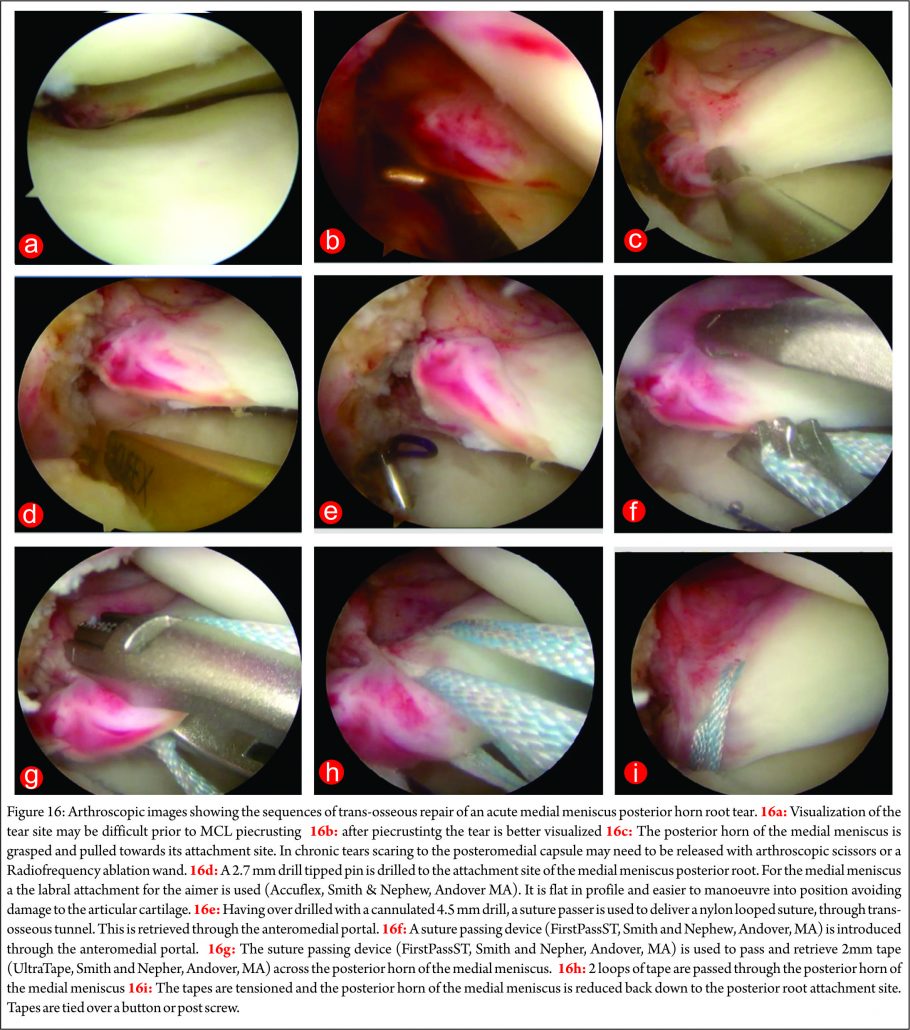

There have been several variants of this technique described (10,68,69,70,71). The advantage of transosseous repair is that a posteromedial arthroscopy portal is frequently not required. As with all cortical suspensory fixation methods, there has been concern about a ‘bungee effect,’ with transosseous tunnel meniscal root repair, and resultant micro-motion at the repair site as a result of the long menisco-suture construct. Feucht et al (65) found that transosseous root repair resulted in 2.2mm +/- 0.5 mm of displacement under cyclical loading in a porcine model compared with 1.3 mm +/- 0.3 mm with suture anchor repair. However, although associated with less micro-motion the technique of placing a suture anchor in a small space while achieving accurate reduction of the tear and preserving the native articular cartilage is technically challenging. Yung et al (67) reported that the suture anchor may loosen and protrude into the joint over time. LaPrade advocates the use of two tibial tunnels for repairs of radial tears of the medial meniscus, siting less gaping after cyclical loading in laboratory conditions, and also significantly stronger ultimate failure loads. (72) We have found that trans-osseous repair allows accurate tear reduction and may also enhance meniscal healing due to the effect of the trans-tibial drilling, with stem cells from the bone marrow entering the intra-articular space (65). It is the senior author’s (JRR) preferred technique of fixation: a standard arthroscopy is performed via anteromedial and anterolateral portals. An accessory anteromedial portal may also be used. In medial repairs, a ‘MCL pie-crusting’ is almost always required to gain sufficient access to the tear and posterior root attachment side (Figure 16 a and b) . This technique has been shown to increase the medial joint opening by 3-4 mm (73,74) and does not result in long term valgus laxity or adverse clinical outcomes (75). The tear is identified and the root attachment repair site is debrided using an RF wand, /shaver / curette to remove scar tissue down to bone to improve healing. Using arthroscopic graspers, the meniscus is pulled towards the attachment site to ensure that the tear may be reduced (Figure 16 c) .Particularly in chronic cases is may be necessary to mobilise the torn meniscus by freeing it from a scar tissue adherence to the the posterior capsule. This may be achieved with arthroscopic scissors and / or RF wand. With the root attachment site prepared and the tear mobilised, a tip aimer is introduced through the antero-medial portal. We utilise an standard ACL tip aimer for lateral meniscus root repairs (Accufex, Smith and Nephew, Andover MA). For medial meniscus posterior horn repairs, however, we use the labral repair attachment for the Accufex aimer which is flat and more easily positioned at the posterior horn root attachment site without injuring articular cartilage (Figure 16d). Tip aimers specific for meniscus root repair are commercially available. A 2.7mm passing pin is drilled to the meniscus root attachment site and then over drilled with a 4.5mm cannulated drill. The drill is left in situ and loop of No1 nylon passing suture passed up the drill with a suture passer, grasped and retrieved through the anteromedial portal (Figure 16e). An 8 mm arthroscopic cannula is placed into the AM portal facilitate suture management and passage. A suture passing device may then be used to pass suture or tape across the meniscus (Figure 16f). The senior author prefers the FirstPass ST device (Smith and Nephew, Andover, MA) as it may be used to pass 2 mm tape (UltraTape, Smith and Nephew, Andover, MA) directly across the meniscus (Figure 16 g). 2 tapes are normal used (Figure 16h) although sometime 3, particularly if there are vertical splits exist in the meniscus (more common with chronic tears and it is necessary to have tape on both sides of the vertical split). For medial meniscus posterior horn root repairs in tight knees, despite an MCL pie crust, access for the suture passing device may be difficult and risk articular cartilage injury. In this situation a 70 degree suture passer (eg AcuPass, Smith and Nephew, Andover, MA) may be used to pass a loop of nylon across the meniscus and this then is used to shuttle the tape across the meniscus. Once passed through the meniscus, the tapes are individually passed down the trans-osseous tunnel. Reduction of the tear is then performed under direct vision (Figure 16 i) by pulling on the tapes which are then tied over a post screw and washer of a button at the external aperture of the trans-osseous tibial tunnel creating a suspensory fixation. In vitro studies have suggested that the use of two parallel tunnels may reduce displacement of the repair (76). Different suture repair techniques have been trailed in the laboratory. Knopf et al. (77) showed that a simple number 2 suture repair using 2 sutures had the lowest pull out strength (Mean approx 60N load to failure). More complex suture patterns (loop suture and modified Kessler) improved pull out strength, however more complex suture patterns are prone to creep and subsequent displacement of the repair. The use of tape improves the pressure distribution on the meniscus and pull out strength (Robinson et al. unpublished data).

Postoperative Rehabilitation

It is important to note that no fixation method is able to restore the strength of the native root attachments. Improved healing rates have been shown in studies where patients were kept non-weight bearing for more than 8 weeks (10,30,48). A slow, conservative post-operative rehabilitation is therefore recommended (77). Most authors advocate full leg extension in either a cast or knee brace (30,32,48,68) for 2 weeks after repair. We allow flexion after this, however this is limited in order minimise stress on the repair to 0-90 degrees for medial meniscal root repairs and 0-70 degrees for lateral (because of the increased antero-posterior excursion in the lateral compartment with knee flexion (78). No loaded flexion greater than 90 degrees or twisting is allowed for 3 months post-op. Return to full activities or sports is generally achieved at 5-6 months post-operatively.

Clinical Outcomes

Studies reporting the outcomes following meniscal root repair are generally limited to case-series or cohort studies. It is perhaps unsurprising that the results are somewhat conflicting (48,65,67,79,80,81) given that the indications for meniscal root repair techniques have evolved and that several different surgical techniques are described. All clinical studies report improvement in subjective outcomes measures at 2-3 years after repair (48,49,67,79,80). Structural outcomes evaluated with MRI or second look arthroscopy have produced conflicting results. Kim et al (50) reported reduced (improved) extrusion following both trans osseous tunnel and suture anchor type repair techniques, but Jung et al (79) found no change in meniscal extrusion after suture anchor repair. Moon et al (80) reported increased meniscal extrusion following the trans-osseous suture technique however, the patient population included people with severe osteoarthritis and a relatively high age (59 years), the poor results may have been attributable to these patient factors, both of which are are considered by some to be contra-indications to meniscal root repair. However other authors (R LaPrade, personal communication 2016) have not shown worse results related to patient age, given the absence of significant arthritic change. Lee et al (49) performed second look arthroscopies in 10 patients who had under gone trans-osseous repair, they found healing in all patients 2 years after repair. Conversely, Seo et al (79) performed second look arthroscopies in 11 patients and found that none had complete healing at 1 year post-operatively. However, 82% of these patients, had chronic meniscal root tears, perceived as having a poorer healing capabilities (76,79). Importantly, the timing of the introduction of weight bearing postoperatively appears to have an important role in the success of healing of the meniscus root repair. Studies in which where weight bearing was allowed prior 6 weeks showed poorer healing rated compared with those in which the introduction of weight-bearing was delayed until to 8 weeks post-operatively (49,50,67).

Conclusions

Meniscus root repair is technically demanding with a steep learning curve. However, techniques are becoming more reproducible and straightforward, particularly as instrumentation to facilitate the procedure has improved and continues to evolve. The basis of treatment is founded upon sound biomechanics principles that have been robustly demonstrated in laboratory studies and the clinical finding that root injuries can lead to rapid joint failure. Meniscus root repair demonstrably improves the meniscal function of load transmission, rendering biomechanics close to the intact state. The objective is to slow or prevent joint deterioration yet, established osteoarthritis would appear to a be a contra-indication to repair. Whilst there are studies showing improvements in patient outcomes following meniscal root repair the impact on delaying the progression of osteoarthritic change remains to be unequivocally demonstrated and it would be wise for enthusiasm in this regard to be moderated until further studies have reported longer-term outcomes.

References

1. Pengas IP, Assiotis A, Nash W, Hatcher J, Banks J, McNicholas MJ. Total meniscectomy in adolescents: a 40-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012 Dec; 94(12):1649-54.

2. Stein T, Mehling AP, Welsch F, von Eisenhart-Rothe, Jager A. A long-term outcome after arthroscopic meniscal repair versus arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for traumatic meniscal tears. Am J Sports Med 2010; 38 (8): 1542-1548.

3. Allaire R, Muriuki M, Gilbertson L, Harner CD. Biomechanical consequences of a tear of the posterior root of the medial meniscus: similar to total meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surgery Am. 2008; 90(9):1922-31.

4. Fox MG. MR imaging of the meniscus: review, current trends and clinical implications. Radiol Clin North Am. 2007;45(6):1033-53.

5. Jones AO, Houang MT, Low RS, Wood DG. Medial meniscus posterior root attachment injury and degeneration: MRI findings. Australas Radiol.2006;50(4):306-313.

6. Lee DW, Ha JK, Kim JG. Medial meniscal root tears: a comprehensive review. Knee Surg Real Res.2014 Sep;26(3):125-134.

7. Bloecker K, Wirth W, Hudelmaier M, Burgkart R, Frobell R, Eckstein F. Morphometric differences between the medial and lateral meniscus in healthy men – a three-dimensional analysis using magnetic resonance imaging. Cells Tissues Organs.2012,195(4):353-364.

8. Fithian DC, Kelly MA, Mow VC. Material Properties and structure-function relationships in the menisci. Clin Orthop Relat Res.1990;252:19-31.

9. Fox Aj, Bedi A, Rodeo SA. The basic science of human knee menisci: structure, composition and function. Sports Health.2012;4(4):340-351.

10. McDevitt CA, Webber RJ. The ultrastructure and biochemistry of meniscal cartilage. Clint Ortho Relat Res.1990;252:8-18.

11. Wirth C. The meniscus-structure, morphology and function. Knee 1996;3:57-58.

12. Andrews SH, Ronsky JL, Rattner JB, Shrive NG, Jamnicky HA. An evaluation of meniscal collagenous structure using optical projection tomography. BMC Med Imaging.2913;13-21.

13. Nicholas SJ, Golant A, Schachter AK, Lee SJ. A new surgical technique for arthroscopic repair of the meniscal root tear. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(12):1433-36.

14. Johnson DL, Swenson TM, Livesay GA, Aizawa H, Fu FH, Harner CD. Insertion-site anatomy of the human menisci: gross, arthroscopic, and topographical anatomy as a basis for meniscal transplantation. Arthroscopy.1995;11(4):386-394.

15. LaPrade CM, Smith SD, Rasmussen MT, Hamming MG, Wijdicks CA, Engebretsen L, Feagin JA, LaPrade RF. Consequences of tibial tunnel reaming on the meniscal roots during cruciate ligament reconstruction in a cadaveric model, Part 1: The anterior cruciate ligament. Am J Sports Med.2015;43(1):200-6.

16. Puyol N, Feucht MJ, Starke C, et al. Meniscal Root tears (ICL6) ESSKA Instructional course lecture book. 65-90.

17. Berlet GC, Fowler PJ. The anterior horn of the medial meniscus: an anatomic study of its insertion.Am J Sports Med.1998;26(4):540-543.

18. Nelson EW, LaPrade RF. The anterior intermeniscal ligament of the knee: an anatomic study.Am J Sports Med.2000;28(1):74-76.

19. Poh Sy, Yew KS, Wong PL. Role of the anterior intermeniscal ligament in tibio-femoral contact mechanics during axial joint loading. Knee 2012;19(2):135-139.

20. Paci JM, Scuderi MG, Werner FW, Sutton LG, Rosenbaum RF, Cannizzaro JP. Knee medial compartment contact pressure increases with release of the type 1 anterior intermeniscal ligament. Am J Sports Med.2009,37(7):1412-1416.

21. Johannsen AM, Civtarese DM, Padalecki JR, Goldsmith MT, Wijdicks CA, LaPrade RF. Qualitative and quantitative anatomic analysis of the posterior root attachments of the medial and lateral menisci. Am J Sports Med.2012;40(10):2342-2347.

22. Zantop CG, Pietrini SD, Westerhaus BD. Arthroscopically pertinent landmarks for tunnel positioning in single-bundle and double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions.Am J Sports Med.2011;39(4):743-752.

23. Kohn D, Moreno B. Meniscus insertion anatomy as a basis for meniscus replacement: a morphological cadaveric study. Arthroscopy 1995,11(1):96-103.

24. LaPrade CM, Ellman MB, Rasmussen MT et al. Anatomy of the anterior root attachments of the medial and lateral menisci: a quantitative analysis.Am J Sports Med.2014;42(10):2286-2392.

25. Naranje S, Mittal R, Nag H Sharma R. Arthroscopic and magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of meniscus lesions in the chronic anterior-ligament deficient knee. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(9):1045-1051.

26. Kidron A, Thein R. Radial tears associated with cleavage tears of the medial meniscus in athletes.Arthroscopy2002;18(3):254-256.

27. Harner CD, Mauro CS, Lesniak BP, Romanowski JR. Biomechanical consequences of a tear of the posterior root of the medial meniscus: surgical technique.J Bone Joint surg Am.2009;91(suppl 2):257-270.

28. Marzo JM, Gurske-DePeiro J. Effects of the medial meniscus posterior horn avulsion and repair on meniscal displacement. Knee2011;18(3):189-192.

29. Vyas D, Harner CD. Meniscus root repair. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev.2012;20(2):86-94.

30. Kim SB, Ha JK, Lee SW et al. Medial meniscal root tear refixation: comparison of clinical, radiologic, and arthroscopic findings with medial meniscectomy. Arthroscopy.2011;27(3):346-354.

31. Papalia R, Vasta S, Franceschi F, D’Adamio S, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Meniscal root tears: from basic science to ultimate surgery. Br Med Bull.2013;106:91-115.

32. Shepard MF, Hunter DM, Davies MR, Shapiro MS, Seeger LL. The clinical significance of anterior horn meniscal tears diagnosed on magnetic resonance images. Am J Sports Med.2002;30(2):189-92.

33. Beldame J, Wajfisz A, Lespagnol F, Hulet C, Seil R. Lateral meniscus lesions on unstable knee. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res.2009;95(8)(suppl 1):S65-S69.

34. Slauterbeck JR, Kousa P, Clifton BC et al. Geographic mapping of meniscus and cartilage lesions associated with anterior cruciate ligament injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Am.2009;91(9):2094-2103.

35. Smith JP, Barrett GR. Medial and lateral meniscal tear patterns in anterior cruciate-ligament deficient knees: a prospective study of 575 tears.Am J Sports Med.2001:29(4):415-419.

36. Thompson WO, Tharte FL, Fu FH, Dye SF. Tibial meniscal dynamics using three dimensional reconstruction of magnetic resonance images. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(3):210-215.

37. llman MB, James EW, LaPrade CM, LaPrade RF. Anterior meniscus root avulsion following intermedullary nailing for a tibial shaft fracture. Knee surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc.2015;23(4):1188-1191.

38. Bin SI, Kim JM, Shin SJ. Radial tears of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus. Arthroscopy 2004;20(4):373-378.

39. Hwang BY, Kim SJ, Lee SW et al. Risk factors for medial meniscus posterior root tear. Am J Sports Med.2012;40(7):1606-1610.

40. Ozkoc G, Circi E, Gonc U, Irgit K, Pourbagher A, Tandogan RN. Radial tears in the root of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus. Arthroscopy.1997;13(6):725-730.

41. Levy IM,Torzilli PA, Warren RF. The effects of medial meniscectomy on antero-posterior motion of the knee. J Bone Joint surg Am.1982;64(6):883-888.

42. Musahl V, Citak M, O’Loughlin PF, Choi D, Bedi A, Pearle AD. The effect of medial versus lateral meniscectomy on the stability of the ACL-deficient knee. Am J Sports Med 2010 Aug 38(8) 1591-7.

43. Lopomo N, Signorelli C, Rahnemai-Azar AA, Raggi F, Hoshino Y, Samuelsson K, Musahl V, Karlsson J, Kuroda R, Zaffagnini S. PIVOT Study Group. Analysis of the influence of anaesthesia on the clinical and quantitative assessment of the pivot shift: a multicenter international study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016 Apr 19.

44. Guan-yang Song, Hui Zhang, Qian-qian Wang et al. Risk factors associated with grade 3 pivot shift after acute anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Am J Sports Med February 2016(44);2:362-369.

45. Brody JM, Lin HM, Hulstyn MJ, Tung GA. Lateral meniscal tear and meniscal extrusion with anterior cruciate ligament tear. Radiology 2006;239:805-810.

46. Shelbourne KD, Roberson TA, Gray T. Long-term evaluation of posterior lateral meniscus root tear left in situ at the time of ACL reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(7):1439-1443.

47. Hulet C, Pereira H, Pereti G, Denti M. Surgery of the meniscus.Springer 2016.

48. Tandogan RN, Taser O, Kayaalp A et al. Analysis of meniscal and chondral lesions accompanying anterior cruciate ligament tears: relationship with age, time from injury and level of sport. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2004;12(4):262-270.

49. Lee HJ, Lim YJ, Kim KB, Kim KH, Song JH. Arthroscopic pullout suture repair of posterior root tear of the medial meniscus: radiographic and clinical results with a 2 year follow-up. Arthroscopy.2009;25(9):951-958.

50. Kim JH, Chung JH, Lee DH, Lee YS, Kim JR, Ryu KJ. Arthroscopic suture anchor repair versus pullout suture repair in posterior root tear of the medial meniscus: a prospective comparison study. Arthroscopy.2011;27(12):1644-1653.

51. Seil R, Duck K, Pape D. A clinical sign to detect root avulsions of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(12):2072-2075.

52. Lee DH, Lee BS, Kim JM et al. Predictors of degenerative medial meniscus extrusion: radial component and knee osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc.2011;19(2):222-229.

53. Lerer DB, Umans HR, Hu MX, Jones MH. The role of meniscal root pathology and radial meniscal tear in medial meniscal extrusion. Skelet Radio.2004;33(10):569-574.

54. Costa CR, Morrison, Carrino JA. Medial meniscus extrusion on knee MRI: is extent associated with severity of degeneration or type of tear? Am J Roentgenol.2004;183(1):17-23.

55. MageeT. MR findings of meniscal extrusion correlated with arthroscopy. J Magn Reson Imaging.2008;28(2):466-470.

56. Ahn JH, Lee YS, Chang JY, Eun SS, Kim SM. Arthroscopic all-inside repair of the lateral meniscus root tear. Knee.2009;16(1):77-80.

57. LaPrade RF, Ho CP, James E, Crespo B, LaPrade CM, Matheny LM. Diagnostic accuracy of 3.0T magnetic resonance imaging for the detection of meniscus posterior root pathology. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(1):152-157.

58. Blackman AJ, Stuart MJ, Levy BA, McCarthy MA, Krych AJ. Arthroscopic Meniscal Root Repair Using a Ceterix NovoStitch Suture Passer. Arthrosc Tech. 2014 Oct; 3(5): e643–e646.

59. LaPrade CM, James EW, Cram TR, Feagin JA, Engebretsen L, LaPrade RF. Meniscal root tears: a classification system based on tear morphology. Am J Sports Med. 2015 Feb;43(2):363-9.

60. West RV, Kim JG, Armfield D, Harner CD. Lateral meniscal root tears associated with anterior curette ligaments injury: classification and management. Arthroscopy.2004;20(1)e32-33.

61. Forkel P, Reuter S, Sprenker F, Achtnich A, Herbst E, Imhoff A, Peterson W. Different patterns of lateral meniscus root tears in ACL injuries: application of a differentiated classification system. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc.2015.23(1):112-118.

62. Koenig JH, Ranawat AS, Umans HR, Difelice GS. Meniscal root tears: diagnosis and treatment. Arthroscopy.2009;25(9):1025-1032.

63. Pagnani MJ, Cooper DE, Warren RF. Extrusion of the medial meniscus. Arthroscopy. 1991;7(3):297-300.

64. Stärke C, Kopf S, Gröbel KH, Becker R. The effect of a nonanatomic repair of the meniscal horn attachment on meniscal tension: a biomechanical study. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(3):358-65.

65. Feucht MJ, Grande E, Brunhuber J, Rosenstiel N, Burgkart R, Imhoff AB, Braun S. Biomechanical comparison between suture anchor and transtibial pull-out repair for posterior medial meniscus root tears. Am J Sports Med.2014;42(1):187-93.

66. Engelsohn E, Umans H, Difelice GS. Marginal fractures of the medial tibial plateau: possible association with medial meniscal root tear. Skeletal Radiol. 2007;36(1):73-76.

67. Yung YH, Choi NH, Oh JS, Victoroff BN. All inside repair for a root tear of the medial meniscus using a suture anchor. Am J Sports Med.2012;40(6):1406-1411.

68. Ahn JH, Wang JH, Lim HC et al. Double transosseous pull out suture technique for transection of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus. Arch Orthop Traums Surg. 2009;129(3):387-392.

69. Ahn JH, Wang JH, Yoo JC, Noh HK, Park JH. A pull out suture for transection of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus: using a posterior trans-septal portal. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(12):1510-1513.

70. Kim YH, Rhee KJ, Lee JK, Hwang DS, Yang YJ, Kim SJ. Arthroscopic pullout repair of a complete radial tear of the tibial attachment site of the medial meniscus posterior horn. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(7):795 e791-794.

71. Marzo JM, Kumar BA. Primary repair of the medial meniscus avulsions: 2 case studies. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(8):1380-1383.

72. Bhatia S, Civitarese DM, Turnbull TL, LaPrade CM, Nitri M, Wijdicks CA, LaPrade RF. A Novel Repair Method for Radial Tears of the Medial Meniscus: Biomechanical Comparison of Transtibial 2-Tunnel and Double Horizontal Mattress Suture Techniques Under Cyclic Loading. Am J Sports Med.2016;44(3):639-45.

73. X Roussignol, O Courage, F Dujardin, F Duparc, C Mandereau. Pie-Crusting du faisceau superficiel du ligament collatéral médial du genou au niveau de son insertion distale tibiale: étude anatomique arthroscopique avec mesure de l’ouverture du compartiment médial fémoro tibial. Revue de Chirurgie Orthopédique et Traumatologique 99(8),e15,2013.

74. Robert HE, Bouguennec N, Vogeli D, Berton E, Bowen M. Coverage of the anterior cruciate ligament femoral footprint using 3 different approaches in single-bundle reconstruction: a cadaveric study analyzed by 3-dimensional computed tomography. Am J Sports Med.2013;41:2375–2383.

75. Claret G, Montañana J, Rios J, Ruiz-Ibán MA, Popescu D, Núñez M, Lozano L, Combalia A, Sastre S. The effect of percutaneous release of the medial collateral ligament in arthroscopic medial meniscectomy on functional outcome. Knee 2016; 23(2):251-255.

76. Bhatia S, LaPrade CM, Ellman MB, LaPrade RF. Meniscal root tears: significance, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(12)3016-3030.

77. Kopf S, Colvin AC, Muriuki M, Zhang X, Harner CD. Meniscal Root Suturing Techniques: Implications for Root Fixation. Am J Sports Med October 2011;39:2141-2146.

78. Johal P, Williams A, Wragg P, Hunt D, Gedroyc W. Tibio-femoral movement in the living knee. A study of weight bearing and non-weight bearing knee kinematics using ‘interventional’ MRI. J Biomech. 2005 Feb;38(2):269-76.

79. Seo HS, Lee SC, Jung KA. Second-look arthroscopic findings after repairs of posterior root tears of the medial meniscus. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(1):99-107.

80. Moon HK, Koh YG, Kim YC, Park YS, Jo SB, Kwon SK. Prognostic factors of arthroscopic pull-out repair for a posterior root tear of the medial meniscus. Am J Sports Med. 2012 May;40(5):1138-43.

81. Kim JH, Chung JH, Lee DH, Lee YS, Kim JR, Ryu KJ. Arthroscopic suture anchor repair versus pullout suture repair in posterior root tear of the medial meniscus: a prospective comparison study. Arthroscopy. 2011 Dec;27(12):1644-53.

| How to Cite this article:. Robinson JR and Jermin PJ. Meniscal Root Tears: Current Concepts. Asian Journal of Arthroscopy Aug – Nov 2016;1(2):35-46. |

Biomechanics and Management of HAGL Lesions in Anterior Instability

Desmond J Bokor, Yuval Arama

Volume 2 | Issue 1 | Jan – Apr 2017 | Page 36 -39

Author: Desmond J Bokor [1], Yuval Arama [1].

[1] Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia

Address of Correspondence

Dr. Desmond Bokor,

Suite 303, 2 Technology Place,Macquarie University. NSW. 2019, Sydney,Australia.

E-mail:desbok@iinet.net.au

Abstract

Humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament is an uncommon but important cause for recurrent anterior instability of the shoulder. It is usually associated with high energy trauma in a slightly older male population with a hyperabduction/axial load mechanism. Associated damage can include avulsion of the glenoid labrum, rotator cuff tears, and bony damage. Diagnosis requires a high index of clinical suspicion, and MR arthrography performed 4-6 weeks post injury is the most reliable investigation. Care should be taken with MRI performed in the first week, as many of the lesions seen at this time will heal. Surgical repair is recommended for recurrent instability or if the patient requirements need them to have a stable shoulder. Repair can be performed using arthroscopic, minopen or full open techniques. Care should be taken when placing sutures through the capsule because of the proximity of the axillary nerve to the inferior capsular edge. Biomechanically, the capsule should be repaired to the medial humeral neck just below the chondral margin. Surgical outcomes are satisfactory in most series reported.

Keywords: Anterior instability, humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament

References

1. Nicola T. Anterior dislocation of the shoulder: The role of the articular capsule. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1942;24:614-616.

2. Wolf EM, Cheng JC, Dickson K. Humeral avulsion of glenohumeral ligaments as a cause of anterior shoulder instability. Arthroscopy 1995;11:600-607.

3. Bokor DJ, Conboy VB, Olson C. Anterior instability of the glenohumeral joint with humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament. A review of 41 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1998;81-B:93-96.

4. Bui-Mansfield LT, Banks KP, Taylor DC. Humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments: The HAGL lesion. Am J Sports Med 2007;35(11):1960-1966.

5. Bui-Mansfield LT, Taylor DC, Uhorchak JM, Tenuta JJ. Humeral avulsions of the glenohumeral ligament: Imaging features and a review of the literature. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2002;179(3):649-655.

6. Field LD, Bokor DJ, Savoie FH. Humeral and glenoid detachment of the anterior inferior glenohumeral ligament: A cause of anterior shoulder instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg1997;6:6-10.

7. Rhee YG, Cho NS. Anterior shoulder instability with humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament lesion. J Shoulder Elbow Surg2007;16:188-192.

8. Bach BR, Warren RF, Fronek J. Disruption of the lateral capsule of the shoulder. A cause of recurrent dislocation. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1988;70:274-276.

9. Turkel SJ, Panio MW, Marshall JL, Girgis FG. Stabilizing mechanisms preventing anterior dislocation of the glenohumeral joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1981;63-A:1208-1217.

10. Bigliani LU, Pollock RG, Soslowsky LJ, Flatow EL, Pawluk RJ, Mow VC. Tensile properties of the inferior glenohumeral ligament. J Orthop Res 1992;10(2):187-197.

11. Norlin R Intraarticular pathology in acute, first-time anterior shoulder dislocation: An arthroscopic study. Arthroscopy 1993;9:546-549.

12. Baker CL, Uribe JW, Whitman C. Arthroscopic evaluation of acute initial anterior shoulder dislocations. Am J Sports Med 1990;18(1):25-28.

13. Gagey O, Gagey N, Boisrenoult P, Hue E, Mazas F. Experimental study of dislocations of the scapulohumeral joint. Rev ChirOrthopReparatriceAppar Mot 1993;79:13-21.

14. Pouliart N, Gagey O. Simulated humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments: A new instability model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg2006;15:728-735.

15. George MS, Khazzam M, Kuhn JE. Humeral avulsion of glenohumeral ligaments. J Am AcadOrthopSurg2011;19:127-133.

16. Gagey OJ, Gagey N. The hyperabduction test. An assessment of the laxity of the inferior glenohumeral ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2000;82-B:69-74.

17. Melvin JS, Mackenzie JD, Nacke E, Sennett BJ, Wells L. MRI of HAGL lesions: Four arthroscopically confirmed cases of false-positive diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol2008;191:730-734.

18. Liavaag S, Stiris MG, Svenningsen S, Enger M, Pripp AH, Brox JI. Capsular lesions with glenohumeral ligament injuries in patients with primary shoulder dislocation: Magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance arthrography evaluation. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2011;21:e291-e297.

19. O’Brien SJ, Neves MC, Arnoczky SP, Rozbruck SR, Dicarlo EF, Warren RF, et al. The anatomy and histology of the inferior glenohumeral ligament complex of the shoulder. Am J Sports Med 1990;18:449-456.

20. Pouliart N, Gagey O. Reconciling arthroscopic and anatomic morphology of the humeral insertion of the inferior glenohumeral ligament. Arthroscopy 2005;21:979-984.

21. Southgate DF, Bokor DJ, Longo UG, Wallace AL, Bull AM. The effect of humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments and humeral repair site on joint laxity: A biomechanical study. Arthroscopy 2013;29(6):990-997.

22. Arciero RA, Mazzocca AD. Mini-open repair technique of HAGL (humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament) lesion. Arthroscopy 2005;21:1152.

23. Bhatia DN, DeBeer JF, van Rooyen KS. The “subscapularis-sparing” approach: A new mini-open technique to repair a humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament lesion. Arthroscopy 2009;25:686-690.

24. Bhatia DN, DasGupta B. Surgical treatment of significant glenoid bone defects and associated humeral avulsions of glenohumeral ligament (HAGL) lesions in anterior shoulder instability. Knee Surg Sports TraumatolArthrosc2013;21:1603-1609.

25. Kon Y, Shiozaki H, Sugaya H. Arthroscopic repair of a humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament lesion. Arthroscopy 2005;21:632.

26. Page RS, Bhatia DN. Arthroscopic repair of humeral avulsion of glenohumeral ligament lesion: Anterior and posterior techniques. Tech Hand Up ExtremSurg 2009;13(2):98-103.

27. Richards DP, Burkhart SS. Arthroscopic humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments (HAGL) repair. Arthroscopy 2004;20 Suppl 2:134-141.

28. Spang JT, Karas SG. The HAGL lesion: An arthroscopic technique for repair of humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments. Arthroscopy 2005;21:498-502.

29. Bhatia DN, de Beer JF. The axillary pouch portal: A new posterior portal for visualization and instrumentation in the inferior ohumeral recess. Arthroscopy 2007;23:1241, e1-e5.

(Abstract) (Full Text HTML) (Download PDF)

Arthroscopic Stabilisation Techniques for Anterior Shoulder Instability

Shiraz Michael Bhatty, Jonathan Herald

Volume 2 | Issue 1 | Jan – Apr 2017 | Page 29 -35

Author: Shiraz Michael Bhatty [1], Jonathan Herald [1].

[1] Fellow, Orthoclinic, Sydney

Address of Correspondence

Dr. Shiraz Michael Bhatty, Fellow, Orthoclinic, Sydney.

Email: shirazbhatty@gmail.com

Abstract

Traumatic anteroinferior dislocation of shoulder in young patients often results in recurrent instability and can be a challenging problem to solve surgically. Treatment of anterior shoulder instability continues to evolve. Arthroscopic shoulder stabilization has become a preferred method of treatment for shoulder instability because reported success rates are parallel to those of open stabilization techniques. This is due to continuing advancement in techniques, instrumentation, improved understanding of the associated pathoanatomy and proper patient selection. In addition to the typical capsulolabral disruptionsseen following a primary dislocation, patients with recurrent instability often have coexistent osseous injury to the humeral head and glenoid. Important considerations during arthroscopy include identifying all pathology, adequate mobilization of the capsulolabral sleeve, retensioning of glenohumeral sleeve and secure anatomic fixation. With advancements in technique and more accurate diagnoses, these outcomes will continue to rise, and patients will more reliably be able to return to prior functioning levels.

Keywords: disclocation of shoulder, pathoanatomy, capsulolabral sleeve.

References

1. Taverna E, Garavaglia G, Ufenast H, D’AmbrosiR, .Arthroscopic treatment of glenoid bone loss. Knee Surg Sports TraumatolArthrosc2016;24:546-556.

2. Lafosse L, Lejeune E, Bouchard A, Kakuda C, Gobezie R, Kochhar T. The arthroscopic Latarjet procedure for the treatment of anterior shoulder instability. Arthroscopy 2007;23:1242.e1-e5.

3. Fabbriciani C, Milano G, Demontis A, Fadda S, Ziranu F, Mulas PD. Arthroscopic versus open treatment of Bankart lesion of the shoulder: A prospective randomized study. Arthroscopy 2004;20:456-462.

4. Grossman MG, Tibone JE, McGarry MH, Schneider DJ, Veneziani S, Lee TQ. A cadaveric model of the throwing shoulder: A possible etiology of superior labrum anterior-to-posterior lesions. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87:824-831.

5. Robinson CM, Dobson RJ. Anterior instability of the shoulder after trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2004;86:469-479.

6. Van Thiel GS, Romeo AA, Provencher MT. Arthroscopic treatment of Antero-inferior shoulder instability. MinnervaOrthop E Traumatol 2010;61(5):393-414.

7. Cole BJ, Millett PJ, Romeo AA, Burkhart SS, Andrews JR, Dugas JR, et al. Arthroscopic treatment of anterior glenohumeral instability: Indications and techniques. Instr Course Lect2004;53:545-558.

8. Purchase RJ, Wolf EM, Hobgood ER, Pollock ME, Smalley CC. Hill-sachs “remplissage”: An arthroscopic solution for the engaging hill-sachs lesion. Arthroscopy 2008;24(6):723-726.

9. Turkel SJ, Panio MW, Marshall JL, Girgis FG. Stabilizing mechanisms preventing anterior dislocation of the glenohumeral joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1981;63:1208-1217.

10. Voos JE, Livermore RW, Feeley BT, Altchek DW, Williams RJ, Warren RF, et al. Prospective evaluation of arthroscopic Bankart repairs for anterior instability. Am J Sports Med 2010;38(2):302-307.

11. Warner JJ, McMahon PJ. The role of the long head of the biceps brachii in superior stability of the glenohumeral joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995;77:366-372.

12. Burkart AC, Debski RE. Anatomy and function of the glenohumeral ligaments in anterior shoulder instability. ClinOrthopRelat Res 2002;32-39.

13. Dumont GD, Russell RD, Robertson WJ. Anterior shoulder instability: A review of pathoanatomy, diagnosis and treatment. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2011;4(4):200-207.

14. Howell SM, Galinat BJ. The glenoid-labral socket. A constrained articular surface. ClinOrthopRelat Res 1989;122-125.

15. Ferrari DA. Capsular ligaments of the shoulder. Anatomical and functional study of the anterior superior capsule. Am J Sports Med 1990;18(1):20-24.

16. Matsen FA 3rd, Chebli C, Lippitt S; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Principles for the evaluation and management of shoulder instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88(3):648-659.

17. Murray IR, Ahmed I, White NJ, Robinson CM. Traumatic anterior shoulder instability in the athlete. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2013;23:387-405.

18. Provencher MT, Bhatia S, Ghodadra NS, Grumet RC, Bach BR Jr, Dewing CB, et al. Recurrent shoulder instability: Current concepts for evaluation and management of glenoid bone loss. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010;92 Suppl 2:133-151.

19. Kim SH, Ha KI, Cho YB, Ryu BD, Oh I. Arthroscopic anterior stabilization of the shoulder: Two to six-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003;85-A:1511-1518.

20. Castagna A, Garofalo R, Conti M, Flanagin B. Arthroscopic Bankart repair: Have we finally reached a gold standard? Knee Surg Sports TraumatolArthrosc2016;24:398-405.

21. Kim SJ, Kim SH, Park BK, Chun YM. Arthroscopic stabilization for recurrent shoulder instability with moderate glenoid bone defect in patients with moderate to low functional demand. Arthroscopy 2014;30:921-927.

22. Kinnard P, Tricoire JL, Levesque R, Bergeron D. Assessment of the unstable shoulder by computed arthrography. A preliminary report. Am J Sports Med 1983;11:157-159.

23. Neviaser TJ. The anterior labroligamentous periosteal sleeve avulsion lesion: A cause of anterior instability of the shoulder. Arthroscopy 1993;9(1):17-21.

24. Lafosse L, Boyle S, Gutierrez-Aramberri M, Shah A, Meller R. Arthroscopic latarjet procedure. OrthopClin North Am 2010;41:393-405.

25. Burkhart SS, De Beer JF. Traumatic glenohumeral bone defects and their relationship to failure of arthroscopic Bankart repairs: Significance of the inverted-pear glenoid and the humeral engaging Hill-Sachs lesion. Arthroscopy 2000;16(7):677-694.

26. HantesM and TsarouhasA (2011). Arthroscopic Treatment of Recurrent Anterior Glenohumeral Instability, Modern Arthroscopy, Dragoo JL (Ed.), InTech, DOI: 10.5772/28374. Available from: http://www.intechopen.com/books/modern-arthroscopy/arthroscopic-treatment-of-recurrent-anterior-glenohumeral-instability

27. Nebelung W, Jaeger A, Wiedemann E. Rationales of arthroscopic shoulder stabilization. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2002;122(8):472-487.

28. Rokous JR, Feagin JA, Abbott HG. Modified axillary roentgenogram. A useful adjunct in the diagnosis of recurrent instability of the shoulder. ClinOrthopRelat Res 1972;82:84-86.

29. Neviaser TJ. The GLAD lesion: Another cause of anterior shoulder pain. Arthroscopy 1993;9:22-23.

30. Torshizy H. MR Imaging of glenoid cartilage lesions. Applied Radiol. 2006;35:14-21.

31. Chandnani VP, Yeager TD, DeBerardino T et al. Glenoid labral tears: Prospective evaluation with MRI imaging, MR arthrography, and CT arthrography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1993;161(6):1229-1235.

32. Oberlander MA, Morgan BE, Visotsky JL. The BHAGL lesion: A new variant of anterior shoulder instability. Arthroscopy 1996;12(5):627-633.

33. Abrams JS. Role of arthroscopy in treating anterior instability of the athlete’s shoulder. Sports Med Arthrosc 2007;15(4):230-238.

34. Boileau P, Villalba M, Héry JY, Balg F, Ahrens P, Neyton L. Risk factors for recurrence of shoulder instability after arthroscopic Bankart repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88(8):1755-1763.

35. Zhu YM, Lu Y, Zhang J, Shen JW, Jiang CY Arthroscopic Bankart repair combined with remplissage technique for the treatment of anterior shoulder instability with engaging Hill-Sachs lesion: A report of 49 cases with a minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med 2011;39(8):1640-1647.

36. Stein D, Laith M, Jazrawi ER, Loebenberg MI. Arthroscopic Stabilization of anterior shoulder instability a historical perspective. Bull Hosp Joint Dis 2001;60(3-4):124-129.

(Abstract) (Full Text HTML) (Download PDF)

Current Trends in Management of Glenoid Bone Loss in Anterior Shoulder Instability

Vikram K Kandhari, Bibhas DasGupta, Deepak N Bhatia

Volume 2 | Issue 1 | Jan – Apr 2017 | Page 20 – 28

Author: Vikram K Kandhari [1], Bibhas DasGupta [1], Deepak N Bhatia [1].

[1] Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Seth GS Medical College, King Edward VII Memorial Hospital, Parel, Mumbai, Maharashtra,

[2] Sportsmed Mumbai, Parel, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

Address of Correspondence

Dr. Deepak N Bhatia,

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Seth GS Medical College, and King Edward VII Memorial Hospital,

Parel, Mumbai – 400 012, Maharashtra, India.

E-mail: shoulderclinic@gmail.com

Abstract

Significant bone defects of glenohumeral joint play an important role in the management of shoulder instability. Bony instability is an important cause of failed soft-tissue repair and recurrent episodes of shoulder dislocations. Bony instability can also be associated with labral (superior and posterior) tears, humeral avulsion of glenohumeral ligament lesions, or rotator cuff tears. Computed tomography (CT) scan with three-dimensional reconstruction is essential for quantification of glenohumeral bone loss. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is reliable for quantification of bone loss, and in addition, demonstrates the soft tissue pathology. Surface area based methods of quantifying glenoid bone loss are more accurate than width based methods. Certain factors important in managing patients with anterior glenohumeral instability include patients’ age, level of sports participation, involvement with contact sports, time of presentation (acute or chronic), and type of bony defect (bony Bankart or attritional bone loss). Soft-tissue reconstruction procedures (labroplasty and remplissage) are usually used in managing patients with nonsignificant bone loss. Patients having significant bone defects of glenoid (>25%) and humerus (off-track/engaging Hill-Sachs lesions) are candidates for open bone grafting of glenohumeral bone defects. Coracoid transfer(Latarjet procedure), either mini-open or arthroscopic gives good functional results and decreases chances of recurrence. Associated lesions should be addressed concomitantly to improve the functional outcome in patients with bony instability of the shoulder. This review presents an evidence-based comprehensive diagnostic and treatment options for patients with bony glenoid deficiency in anterior shoulder instability.

Keywords: Shoulder instability, Hill-Sachs lesion,Labroplasty, Latarjet procedure,Remplissage, Glenoid bone loss, Bony Bankart.

References

1. Burkhart SS, De Beer JF. Traumatic glenohumeral bone defects and their relationship to failure of arthroscopic Bankart repairs: Significance of the inverted-pear glenoid and the humeral engaging Hill-Sachs lesion. Arthroscopy 2000;16(7):677-694.

2. Hovelius L. Incidence of shoulder dislocation in Sweden. ClinOrthopRelat Res 1982;166:127-131.

3. Taylor DC, Arciero RA. Pathologic changes associated with shoulder dislocations. Arthroscopic and physical examination findings in first-time, traumatic anterior dislocations. Am J Sports Med 1997;25(3):306-311.

4. Fujii Y, Yoneda M, Wakitani S, Hayashida K. Histologic analysis of bony Bankart lesions in recurrent anterior instability of the shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2006;15(2):218-223.

5. Hill HA, Sachs MD. The grooved defect of the humeral head a frequently unrecognized complication of dislocations of the shoulder joint. Radiology1940;35(6):690-700.

6. Calandra JJ, Baker CL, Uribe J. The incidence of Hill-Sachs lesions in initial anterior shoulder dislocations. Arthroscopy 1989;5(4):254-257.

7. de Beer J, Bhatia DN. Shoulder injuries in rugby players. Int J Shoulder Surg 2009;3(1):1-3.

8. Arrigoni P, Huberty D, Brady PC, Weber IC, Burkhart SS. The value of arthroscopy before an open modified latarjet reconstruction. Arthroscopy 2008;24(5):514-519.

9. Bhatia DN, DasGupta B. Surgical treatment of significant glenoid bone defects and associated humeral avulsions of glenohumeral ligament (HAGL) lesions in anterior shoulder instability. Knee Surg Sports TraumatolArthrosc 2013;21(7):1603-1609.

10. Bushnell BD, Creighton RA, Herring MM. Bony instability of the shoulder. Arthroscopy 2008;24(9):1061-1073.

11. Bushnell BD, R. Creighton A, Herring MM. The Bony Apprehension Test for instability of the shoulder: A prospective pilot analysis. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery 2008;24(9):974-982.

12. Edwards TB, Boulahia A, Walch G. Radiographic analysis of bone defects in chronic anterior shoulder instability. Arthroscopy 2003;19(7):732-739.

13. Rokous JR, Feagin JA, Abbott HG. Modified axillary roentgenogram. A useful adjunct in the diagnosis of recurrent instability of the shoulder. ClinOrthopRelat Res 1972;82:84-86.

14. Garth WP Jr, Slappey CE, Ochs CW. Roentgenographic demonstration of instability of the shoulder: The apical oblique projection. A technical note. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1984;66(9):1450-1453.

15. Pavlov H, Warren RF, Weiss CB Jr, Dines DM. The roentgenographic evaluation of anterior shoulder instability. ClinOrthopRelatRes 1985;194:153-158.

16. Gerber C, Nyffeler RW. Classification of glenohumeral joint instability. ClinOrthopRelat Res 2002;400:65-76.

17. Murachovsky J, Bueno RS, Nascimento LG, Almeida LH, Strose E, Castiglia MT, et al. Calculating anterior glenoid bone loss using the Bernageau profile view. Skeletal Radiol 2012;41(10):1231-1237.

18. Itoi E, Lee SB, Amrami KK, Wenger DE, An KN. Quantitative assessment of classic anteroinferior bony Bankart lesions by radiography and computed tomography. Am J Sports Med 2003;31(1):112-118.

19. Sugaya H. Techniques to evaluate glenoid bone loss. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2014;7(1):1-5.

20. Ito H, Takayama A, Shirai Y. Radiographic evaluation of the Hill-Sachs lesion in patients with recurrent anterior shoulder instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2000;9(6):495-497.

21. Bhatia DN, de Beer JF, du Toit DF. Coracoid process anatomy: Implications in radiographic imaging and surgery. ClinAnat 2007;20(7):774-784.

22. Bhatia DN, Dasgupta B, Rao N. Orthogonal radiographic technique for radiographic visualization of coracoid process fractures and pericoracoid fracture extensions. J Orthop Trauma 2013;27(5):e118-e121.

23. Goldberg RP, Vicks B. Oblique angled view for coracoid fractures. Skeletal Radiol 1983;9(3):195-197.

24. Griffith JF, Antonio GE, Tong CW, Ming CK. Anterior shoulder dislocation: Quantification of glenoid bone loss with CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003;180(5):1423-1430.

25. Sekiya JK, Cutuk A. Humeral head defects – Biomechanics, measurements, and treatments. In: Provencher MT, Romeo AA, editors. Shoulder Instability: AComprehensive Approach. Philadelphia, PA:Elsevier, Saunders; 2012.p. 234-247.

26. Saito H, Itoi E, Minagawa H, Yamamoto N, Tuoheti Y, Seki N. Location of the Hill-Sachs lesion in shoulders with recurrent anterior dislocation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2009;129(10):1327-1334.

27. Miniaci A, Gish M. Management of anterior glenohumeral instability associated with large Hill-Sachs defects. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg2004;5(3):170-175.

28. Lee RK, Griffith JF, Tong MM, Sharma N, Yung P. Glenoid bone loss: Assessment with MR imaging. Radiology 2013;267(2):496-502.

29. Huijsmans PE, Haen PS, Kidd M, Dhert WJ, van der Hulst VP, Willems WJ. Quantification of a glenoid defect with three-dimensional computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging: A cadaveric study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2007;16(6):803-809.

30. Bencardino JT, Gyftopoulos S, Palmer WD. Imaging in anterior glenohumeral instability. Radiology 2013;269(2):323-337.

31. Simão MN, Nogueira-Barbosa MH, Muglia VF, Barbieri CH. Anterior shoulder instability: Correlation between magnetic resonance arthrography, ultrasound arthrography and intraoperative findings. Ultrasound Med Biol 2012;38(4):551-560.

32. Bigliani LU, Newton PM, Steinmann SP, Connor PM, Mcllveen SJ. Glenoid rim lesions associated with recurrent anterior dislocation of the shoulder. Am J Sports Med 1998;26(1):41-45.

33. Itoi E, Lee SB, Berglund LJ, Berge LL, An KN. The effect of a glenoid defect on anteroinferior stability of the shoulder after Bankart repair: A cadaveric study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000;82(1):35-46.

34. Lo IK, Parten PM, Burkhart SS. The inverted pear glenoid: An indicator of significant glenoid bone loss. Arthroscopy 2004;20(2):169-174.

35. Greis PE, Scuderi MG, Mohr A, Bachus KN, Burks RT. Glenohumeral articular contact areas and pressures following labral and osseous injury to the anteroinferior quadrant of the glenoid. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2002;11(5):442-451.

36. Flatow EL, Miniaci A, Evans PJ, Simonian PT, Warren RF. Instability of the shoulder: Complex problems and failed repairs: Part II. Failed repairs. Instr Course Lect 1998;47:113-125.

37. Yamamoto N, Itoi E, Abe H, Minagawa H, Seki N, Shimada Y, et al. Contact between the glenoid and the humeral head in abduction, external rotation, and horizontal extension: A new concept of glenoid track. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2007;16(5):649-656.

38. Huysmans PE, Haen PS, Kidd M, Dhert WJ, Willems JW. The shape of the inferior part of the glenoid: A cadaveric study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2006;15(6):759-763.

39. Bhatia S, Saigal A, Frank RM, Bach BRJr, Cole BJ, Romeo AA, et al. Glenoid diameter is an inaccurate method for percent glenoid bone loss quantification: Analysis and techniques for improved accuracy. Arthroscopy 2015;31(4):608-614.

40. Baudi P, Campochiaro G, Rebuzzi M, Matino G, Catani F. Assessment of bone defects in anterior shoulder instability. Joints 2013;1(1):40-48.

41. Dumont GD, Russell RD, Browne MG, Robertson WJ. Area-based determination of bone loss using the glenoid arc angle. Arthroscopy 2012;28(7):1030-1035.

42. Burkhart SS, Debeer JF, Tehrany AM, Parten PM. Quantifying glenoid bone loss arthroscopically in shoulder instability. Arthroscopy 2002;18(5):488-491.

43. Detterline AJ, Provencher MT, Ghodadra N, Bach BR Jr, Romeo AA, Verma NN. A new arthroscopic technique to determine anterior-inferior glenoid bone loss: Validation of the secant chord theory in a cadaveric model. Arthroscopy 2009;25(11):1249-1256.

44. Bakshi NK, Patel I, Jacobson JA, Debski RE, Sekiya JK. Comparison of 3-dimensional computed tomography-based measurement of glenoid bone loss with arthroscopic defect size estimation in patients with anterior shoulder instability. Arthroscopy 2015;31(10):1880-1885.

45. Rowe CR, Zarins B, Ciullo JV. Recurrent anterior dislocation of the shoulder after surgical repair. Apparent causes of failure and treatment. J Bone Joint SurgAm 1984;66(2):159-168.

46. Montgomery WH Jr, Wahl M, Hettrich C, Itoi E, Lippitt SB, Matsen FA 3rd. Anteroinferior bone-grafting can restore stability in osseous glenoid defects. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87(9):1972-1977.

47. Hardy P. Bony Lesions Influence on the Result of the Arthroscopic Treatment of Glenohumeral Instability. Symposium: Shoulder Instability-Limits of Arthroscopic Surgery: Bone Deficiency, Shrinkage, Acute Instability. Presented at the 5th International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine Congress, March 10-14, 2003; Auckland, New Zealand.

48. Forsythe B, Frank RM, Ahmed M, Verma NN, Cole BJ, Romeo AA, et al. Identification and treatment of existing copathology in anterior shoulder instability repair. Arthroscopy 2015;31(1):154-166.

49. Balg F, Boileau P. The instability severity index score. A simple pre-operative score to select patients for arthroscopic or open shoulder stabilisation. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007;89(11):1470-1477.

50. Di Giacomo G, Itoi E, Burkhart SS. Evolving concept of bipolar bone loss and the Hill-Sachs lesion: From “engaging/non-engaging” lesion to “on-track/off-track” lesion. Arthroscopy 2014;30(1):90-98.

51. Yamamoto N, Itoi E. Osseous defects seen in patients with anterior shoulder instability. ClinOrthopSurg 2015;7(4):425-429.

52. Bhatia DN, DeBeer JF. Management of anterior shoulder instability without bone loss: arthroscopic and mini-open techniques. Shoulder Elbow 2011;3:1-7.